On November 23rd, 1980, at 7.30 PM, in Southern Italy, the earth trembled; as a result, 90 seconds later a part of Italy of 6,600 sq. mi. (1.3 times the surface of Connecticut) was almost completely swept away from any map.

Where is Irpinia?

Irpinia is the name commonly used for the province of Avellino, a town of almost 60,000 in Campania, about 50 Km away from Naples, and 40 Km from the Amalfi Coast.

Irpinia was the area most severely hit by the earthquake, and so for all the press info about the tragedy, it started to be called the Irpinia earthquake.

The official total bill of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake was 2,914 deaths, more than 10,000 injured and 300,000 homeless. Roads, railways, water pipes, electric pipes: the majority of the area’s infrastructures were destroyed or damaged.

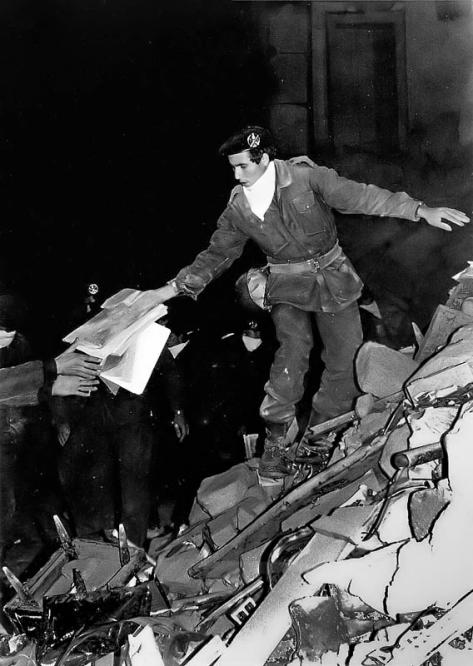

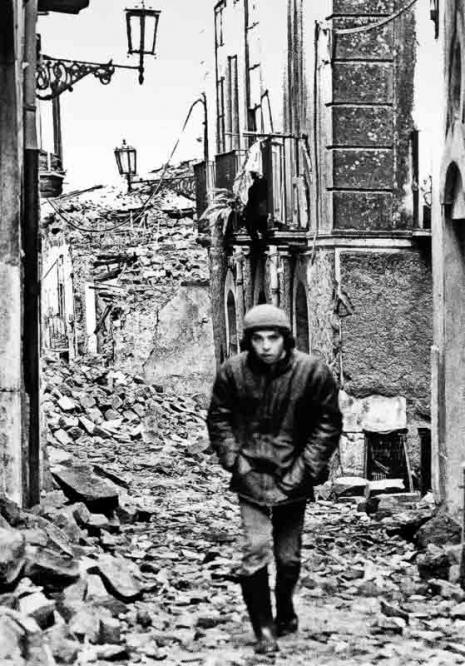

The aftermath of the 1980 earthquake

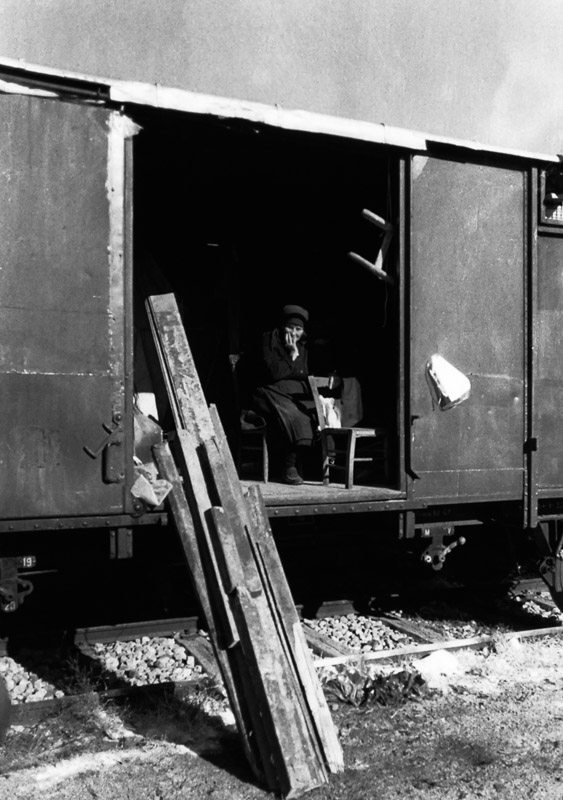

Those were days of grief, fear and freeze. Together with the earthquake came the winter and that wasn’t pleasant for the homeless who were hosted in tents.

It was dark when the 1980 Irpinia earthquake hit, and only the day after the light made it possible to understand how big the destruction was, but the area was so vast and partially remote that it took three days to have a complete idea of the dimensions of the tragedy.

Mr Stählin and me

On November 23rd, 1980 I was also homeless. The building that hosted the flat where I used to live was still standing but damaged. The flat was on the sixth and top floor of that tall and narrow building. Authorities told us we were not authorized to live there. But we had the chance to go up just once to collect warm clothes, blankets and our valuables. I forgot the blankets but took my Pentax and all my B&W Ilford FP4 film rolls.

The following days were spent mainly searching for survivors or corpses. I had my camera with me and used it every time I could.

When he heard the news about the earthquake, Charles Stählin, a Swiss engineer, loaded his car with his newly built gear and, together with his daughter, left the tiny, peaceful village of Oberengstringen and drove straight to Avellino.

His invention was a sound receiver and amplifier that could be placed between the debris to hear sighs, cries, or any noise that could evidence the presence of survivors.

Today, thirty years later, it’s a very common gear among rescue teams, but at those times it was something new and rare. Those were the times when the research was held mainly with dogs and removing carefully the debris.

Mr Stählin was slightly lame in one leg, but perfectly able to take care of himself and the daughter; he had no hint about Italian that’s why he needed an interpreter. At the crisis unit headquarters, somebody chose a guy who studied German at the college. It was me.

The search

Just the time to introduce ourselves and we were already driving in the direction of the most severely hit area: in Lioni the roads were cracked, the railway station’s building collapsed, and the rails were crowded with freight wagons used to host the homeless. The Town Hall was also destroyed.

In Bisaccia, a great amount of the old buildings were destroyed but also the modern hospital collapsed in a vertical shift: therefore the collapsed floors were piled up and among them were the beds, crushed by the debris. The rescuers had to work with the oxyhydrogen flame to create a path and reach the corpses. The smell all around was unbearable.

In Teora the coffins were piled up at the edge of the road, ready to be filled.

Sant’ Angelo Dei Lombardi was almost destroyed and an emergency hospital had been installed in the football stadium.

The destruction

But we saw the real, absolute destruction once we arrived in Conza della Campania: there were only rocks and stones where once buildings and houses stood. No single building was still intact. The church collapsed when it was full of people (it was a Sunday when the earthquake hit) and many faithful were killed. Only the water tank still stood exactly on the top of the hill where once the town was, incongruous, overlooking a landscape of rubble and death.

Frankly speaking, I didn’t have many chances to be helpful with my language skills. My knowledge of German was useful in talking with Mr Stählin, his daughter and the German soldiers who came to rescue with trucks, field hospitals, doctors and helicopters. But my presence on the field was important because Mr Stählin needed somebody to help him place his microphone in the right spots, and this means under the debris of a collapsed building, between the stones that filled up a cellar and things like that. That was my duty. But I also aimed to shoot photographs.

We lived that life for more than one week and finally came back to Avellino. Mr Stählin’s help made iy possible to rescue a dozen of people. For this reason, years later, he was granted an honorary title.

Photographs and memories

Of those tragic days of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake, I’ve kept several hundred black and white prints, processed in hard conditions, developed and printed with such gears as I could find, stored carefully and finally scanned to grant them a longer life. What I show here is a selection of them. There is no artistic aim in these pictures; they are just a document of a tragic piece of history of Italy, a symbol of respect of the memory of the thousands of victims of that terrible day and a symbol of closeness with all other persons who – in Italy and the whole world – have experienced the same terrible feelings.

Did you like it? For more beautiful photos and travel stories, just use the menu above and browse the site. Do you know that you can send any of my images as an e-card?

Just choose your favourite image, press the e-card- button down on the right and that’s it, the pic is ready to be sent to your loved ones! Just give it a try, it’s fun and it’s free!

Would you also like to read all my upcoming travel stories? Just click here and subscribe to my newsletter.

I will mail you only when I release a new article. Your information is 100% safe and never shared with anyone